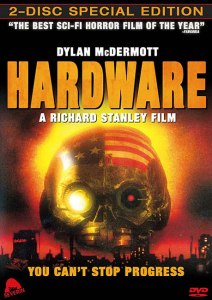

GUEST POST: A LOVE LETTER TO RICHARD STANLEY’S “HARDWARE”

I can’t imagine there’s a writer out there who doesn’t have a list, secret or otherwise, of things that were just that bit more influential than others. Influences are out there, influencing (it’s what they do), all the time. Some are fleeting, doing no more than setting one’s thoughts adrift in a particular direction for a while. Some are whimsical, leading to a pleasant few hours of idle musing, which may or may not evolve into something new later on.

And some punch you in the face, grab your guts in both fists and squeeze the life out of you, so the person you become is, in some ineffable quality, different.

We don’t always embrace these influences willingly, I think. Sometimes we react to them as our immune system does to an invading virus, calling forth our defenses. Thus it was for me and Richard Stanley’s seminal work HARDWARE.

HARDWARE for those of you who have not seen it, is a British-American sci-fi horror starring Dylan McDermott (now better known for American Horror Story and Stalker), Stacey Travis, John Lynch, Iggy Pop (yes), William Hootkins (who also turns up in one of my other favourites, Death Machine), Carl McCoy of Fields of the Nephilim, and Lemmy. Yes, that Lemmy.

It’s based on a 1980 short strip called SHOK!, from the British science fiction comic 2000A.D., written by Steve MacManus (Strontium Dog, Rogue Trooper) and Kevin O’Neill (Nemesis the Warlock, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen). Stanley developed the bare bones of the original short into a nightmare vision of a post-apocalyptic world, in which empty-eyed nomads sift through radioactive wastelands to find scraps to sell on the black market. Here, risking infertility as a labourer on the asteroid belt is one of the better options in a practically non-existent employment market, and, as a bonus, saves the government the bother and expense of state-sponsored sterilisation. Locking oneself in an apartment where the security system was installed by the creepy, lecherous, peeping tom, would-be rapist neighbour (Hootkins) rates quite high on the personal safety front. This is a world in which the conservative liberal dream of self-interest above all else is taken to its extreme, where nobody does anything for anyone unless there’s something in it for them, and the government’s sole job is to reduce the state burden on the 1%.

Enter Mo, a former soldier whose damaged humanity is clear in the form of a prosthetic hand that looks like it belongs on an android. He is returning home to his artist girlfriend, Jill, from whom he has been parted for long enough that he’s worried she won’t have waited for him, even though toxic masculinity makes him insist to his psychedelic-abusing best mate Shades that she needs him to keep her warm and safe. “She sleeps better when I’m around.”

He wants to bring her a present, fulfilling the traditional role of hunter gatherer providing for his woman, even though she already has everything she needs and is perfectly capable of surviving on her own–just as well, as he’s hardly ever there.

And she’s going to be glad of her self-reliance later.

He stops at his friend’s black market junkyard on the way there to sell a few things, where he meets a dune drifter and buys some robot parts for Jill, not realising that the parts belong to a M.A.R.K. 13 genocide robot.

For in those days shall be affliction, such as was not from the beginning of the creation which God created unto this time, neither shall be. And except that the Lord had shortened those days, no flesh should be saved: but for the elect’s sake, whom he hath chosen, he hath shortened the days.

Or, as Mo puts it:

“See these mighty buildings. It all shall be thrown down and shattered to splinters. The earth will shake, rattle and roll. The masses will go hungry, their bellies bloat. These are the birth pains. No flesh shall be spared.”

No flesh shall be spared…

Cue claustrophobic shenanigans.

I was first introduced to the film by the person whom I was later to marry—we joke that he introduced me to spices and HARDWARE, I introduced him to coffee—and the first time I watched it I hated it. There was no reason I could give for that hatred. I watched it probably three or four more times before I began to love it. This does not happen very often. While there are certainly films I have detested on first exposure, only to mellow later, this is usually a result of overly-optimistic expectations being dashed by the Hollywood profit engine (cough, Prometheus). By contrast, HARDWARE was made on a relatively tiny budget, and still manages to depict Mega City 1 more faithfully than 2012’s Dredd (Karl Urban in his Wolverine publicity phase, there).

But my love for HARDWARE has nothing to do with its 2000A.D. ancestry, nor its kick-ass, self-rescuing, motherhood-rejecting female protagonist. My love for this film resides in its fractal storytelling.

There’s a scene, a ridiculously over-dramatic descent into death, to the soul-shivering, ecstatic grief of Rossini’s version of that beautiful hymn to Mary, Stabat Mater (“the Grieving Mother”):

Stabat Mater dolorosa iuxta crucem lacrimosa dum pendebat Filius.

At the cross her station keeping, stood the mournful mother weeping, close to Jesus to the last.

Every single aspect of this death scene has been foreshadowed, and foreshadows, some other relevation in this film. And if you needed reminding, Stanley uses fractal imagery within the hallucination. The whole film is like that, layer upon layer of reflection and internal reference. Every time I watch it (and I must have seen it dozens of times now), I find something I hadn’t noticed before. There’s nothing wasted in this film: not the dead woman on the stairs, wailing child still handcuffed to her wrist (a reflection and echo of the Stabat Mater); not Jill’s offhand comment about what her spider does to the bugs she catches for it; not the fritzy air conditioning; not the seemingly throwaway newscasts; not the taxi driver’s grumble about weapons escalation.

The writers I admire are those who offer surprisal saturation. Each sentence, each word, contains information. This is not the same as brevity, although it can be mistaken for it. It may resemble scant, sparse prose, but it’s not that at all. I’m equally enamoured of effusive, flowing writing, as long as the information content is high and it’s not using thirty words to offer the same information as ten.

It’s possible to be poetic without resorting to syntactic indulgence.

Stanley, in HARDWARE, is indulgent, but not syntactically so. Everything has a purpose. Everything is adding nuance and depth to the message he conveys. There is very little exposition and none is needed. Everything is there, with commentary riffing off the brilliant Simon Boswell soundtrack.

Stanley belongs in a select group of surprisal-heavy writer-directors, along with the likes of Peter Greenaway, and it was that which punched me in the face and tied my guts into new knots. Now, as a writer myself, I obsess over surprisal in my stories. That’s partly Stanley’s fault, with his layers of meaning and constant thematic echoes.

It’s easy to watch HARDWARE and see nothing more than a robot monster movie, with a creepy fat guy and a rocking soundtrack (the Public Image Ltd track “The Order of Death” was rudely hijacked by The Blair Witch Project some years later). It’s so much more than that.

But you have to look deeper than the plot.

I met Stanley a few years back, albeit in passing, when I finally had the opportunity to see HARDWARE on the big screen, at a special showing in Edinburgh. There he was, in his trademark hat, and I said hello, thanks, love the film. I wish I’d been able to express to him how much this film means to me. Not because I like horror, or science fiction, although I do like both these things; not even because this is, as Birth. Movies. Death. puts it, “a Heavy Metal Piece of Feminist Artwork”. Rather because he fulfilled the unspoken role of everyone who takes it upon themselves to tell stories: influencing the future storytellers in the audience.

Thanks, Mr Stanley.

* * *

Sam Fleming is a spec-fic writer and scientist living in the North East of Scotland, where it’s all too easy to believe there are things living in the seafog locally known as the Haar. Sam’s stories have been published in Black Static, and by Dagan Books and NewCon Press. Find her at www.ravenbait.com and ravenfamily.org/sam.